• Here I am putting shredded paper into a public compost bin in Myrtle street, Chippendale, an inner city suburb in Sydney, Australia

How growing urban food is ending food waste

By Kristina Ulm

Nature knows no waste. We can turn ‘food waste’ to a resource to grow food. But how? Let me tell you a story about moving to other planets to explain.

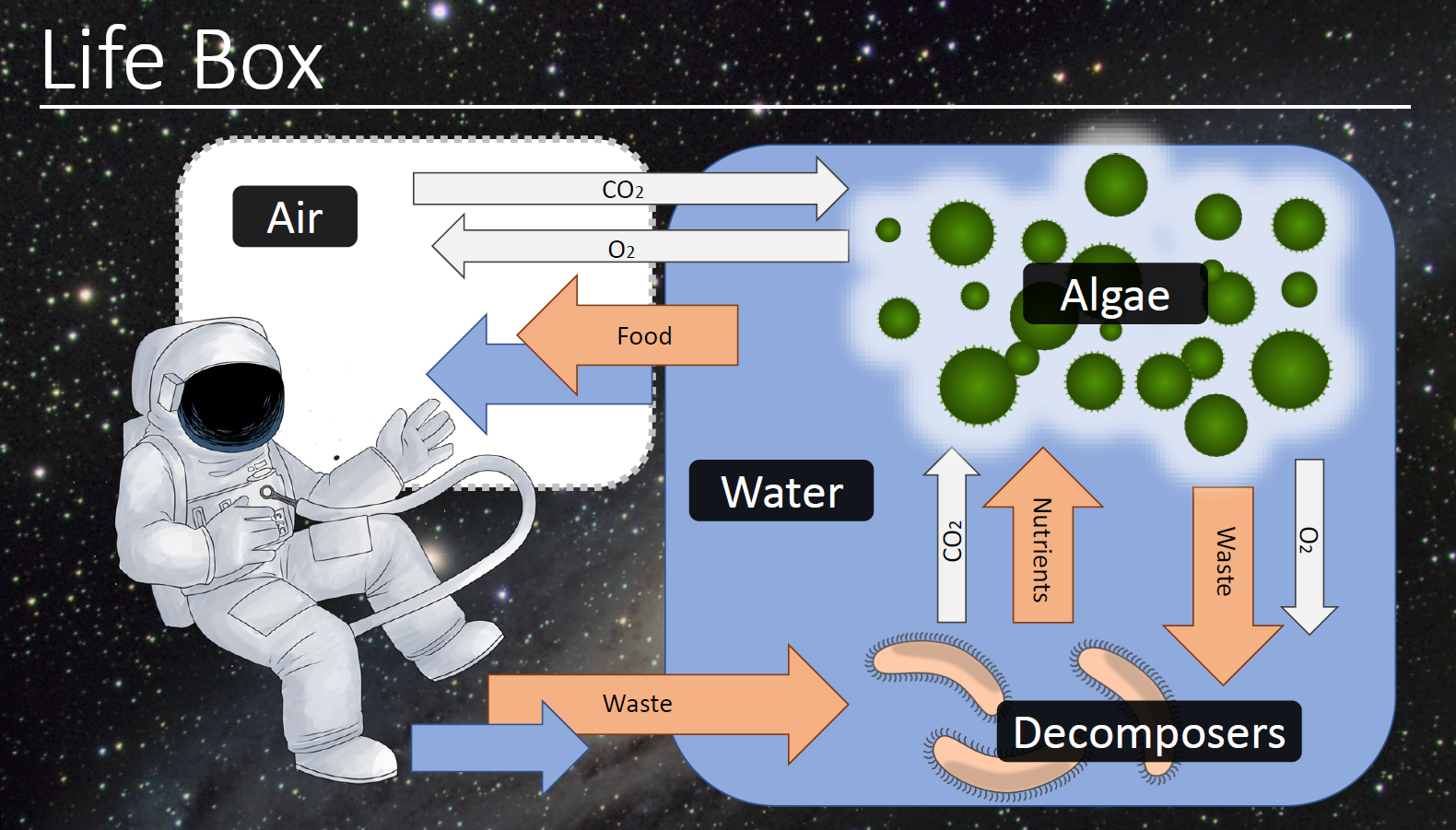

Imagine you are an astronaut. What most basic things will you need to start a new life on another planet? We can’t take too much weight with us. Imagine a small box – A Life Box, to keep us alive. What do we humans need to survive?

Did you think of water and air? Immediately we realize that we need to breathe oxygen and drink water daily. Next, you probably thought of food. We need to eat to survive. But here comes the tricky bit. What can we fit in a small box that we can eat but it would also grow fast enough to sustain us for a long time? No, sorry, not chicken nuggets or cheese sandwiches. They don’t grow by themselves in a box. Plants? - Yes, that is going the right direction. And the easiest form of plant to take to outer space is algae. So far, our Life Box contains air, water, and algae for food, the essentials humans need to survive.

• Life Box – Is that all we need?

But what about surviving long-term? Can our box sustain us by itself?

You probably already heard that plants, including our algae, produce the oxygen we need. And plants use the carbon dioxide we breathe out. A win-win relationship! Water is a bit more complicated. But I assure you: as long as our Life Box stays closed the water will continue to cycle through the air, plants, and us and we will not go thirsty.

But some of us may forget that plants need to be fed, too. If you are a gardener, you might suggest soil or fertiliser to take along. But these would need to be reproduced again. How? Who makes these? The magic word here is decomposers. Decomposers are living beings that process organic matter, like dead parts of plants or our poo into new nutrients for plants. You likely met one larger decomposer, the earth worm. The smallest decomposers are a variety of bacteria. Between a million and a billion of them are estimated to be in just one gram of soil. 1

To keep our Life Box light, we don’t take a lot of soil with us. Decomposing bacteria that live in water is sufficient. And highly necessary - only with them we can close the nutrient cycle that feeds the plants and then us. Nature knows no waste. The waste of one living being is the food of another.

• Complete life box

Decomposers eat our unwanted organic material, and plants live off the waste products of decomposers. I see random seeds sprout in my worm farm. The poo of the earth worms is a beautiful dark nutritious soil!

I have to admit that the ecological system is more complex than my description above. If you have deep knowledge about ecology, this little story will seem very simplified to you. While I focussed on the key elements and relationships, there are many more nutrient and energy processes involved. It is in fact so complex that the international project ‘MELiSSA’, led by European Space Agency (ESA) tries to create such a ‘Life Box’ since decades. Only slowly are they getting closer to their goal to recreate an ecosystem that could support human life long-term in outer space. See description here.

I told this Life Box story to some friends who were already growing herbs and eggplant on their tiny balcony. “What?”, they said, “we can turn our banana and potato peels into soil for our plants by composting?” A week after, they started composting their ‘food waste’. Because once we understand how crucial decomposers are for sustaining our ecosystems, we understand the importance of composting. Composting means feeding decomposers.

We should stop calling food waste ‘waste’ because it isn’t waste, it is food for decomposers that feed our food. What does this mean? We do have an alternative to agriculture that relies on fertilisers produced using non-renewable resources and emitting tons of greenhouse gases. We can compost and use egg shells, potato peels and wilted leaves as ‘food’. Food for the next living beings in the nutrient cycle: the decomposers.

Food waste pollution graphed as a country = third largest climate polluting country after China and the US

It all sounds great in theory but what does it mean in practice? Can a city person like me, who never grew a vegetable herself, do it? I started a worm farm earlier this year and my daughter painted ‘worm plaza’ on it. We jokingly called them our pets. But I must admit, it is not as easy as I thought. They are like pets you have to take care of. I accidentally killed dozens of earth worms by letting the worm farm go dry in the heat. Those poor worms tried to escape but didn’t get too far on our balcony. I am still learning. While gardening and composting with Michael I asked him about worm care advice. I am very grateful for all I have learned from Michael while gardening the streets of Chippendale together. He also showed me that composting can be fun. Who wouldn’t like to shred newspaper, add it to a rotating compost bin and whirl it around in circles? I greatly enjoyed it. The shredded newspaper absorbs excess moisture in the compost and provides carbon for the decomposing process.

• The fun in composting - shredding newspapers and spinning the bin

I’m also impressed by the different methods of composting that people can use in Chippendale. Compost seats, colourful bins, worm farms and tube composters. Some of them need more maintenance than others. Michael spends hours every week to move food scraps from the compost bins that are not connected to the soil underneath, like the rotating bin, to the compost bins in his garden (see image four). After some time, the finished compost gets used in the garden beds on the footpath.

Many of us lack the time, knowledge and commitment to maintain compost containers. Which is why I believe that we need a variety of communal options to turn food scraps to soil. Every one of us has something different to contribute: time or knowledge or food scraps. Together we can create soil from ‘food waste’ and use it to grow food locally. All different kinds of urban farming can benefit from our food scraps and help end food waste: community gardens, market gardens, school gardens, rooftop farms and verge gardens. Any citizens, businesses, governments and local organisations can be involved.

• Regular composting takes time; over 300 kg of food is composted each week in Chippendale’s road gardens taking a few hours of maintenance by locals

In sum, if we want to feed people we need to feed the soil first. Share the story of taking a small ecosystem to outer space to explain the importance of the often forgotten decomposers.

• Worm farms and compost seats in the streets of Chippendale, NSW

To hear more on Chippendale’s new composting projects and experience the interactive astronaut story, come to the community event at Knox Street bar in Chippendale on 21 January, 2021.

You can be in the room or at home on your computer and join the conversation from home; I’ll be talking about my research at the event.

Sign up for the in person or online event here.

• Knox Street Bar event in January - join online or be there

I would like to acknowledge the source of the amended astronaut story: Mc Harg’s book Design with Nature 2, in which he explains how and why the design of our cities and regions should be based on ecological cycles. It is a highly recommendable classic to anyone involved in designing and planning human built environments, like landscape architects or regional planners.

References

1. Whitman, W. B., Coleman, D. C. & Wiebe, W. J. Prokaryotes: The unseen majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 6578–6583 (1998).

2. McHarg, I. L. Design with nature. (New York : J. Wiley; Originally published: Garden City, N.Y. : Published for the American Museum of Natural History by the Natural History Press, 1969., 1992).