• Andra Gutierrez, writing from her home in Arizona while interning with Sustainable House

Hello! My name is Andra Gutierrez.

I’m currently a senior at Arizona State University majoring in Sustainability. I am remotely interning with Sustainable House for the Fall 2021 semester. I am of the Akimel O’otham (River People) tribe from the Keli Akimel O’otham Jeved (Gila River Indian Community or GRIC) which is a Native American reservation south of Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

Here’s a little history about tribal community here.

My tribal community encompasses about 372,000 acres of land and has a population of little over 14,000. GRIC is made up of seven villages (or Districts): Uhs-Kehk (District 1); Hashan Kehk (district 2), Gu’u Ki (District 3), Stontonic / Valin Thak (District 4); Vah-ki (District 5); Komatke (District 6) and Maricopa Village (District 7). I live in the village of Valin Thak (District 4).

Before reservations, the ancestral lands of O’otham spanned from North of Phoenix to Sonora, Mexico.

We believe we are the descendants of the Hohokam (ones who came before us) who existed during pre-historic times circa 300 B.C. My community is home to two tribes: the Akimel O’otham (River People) and the Pee Posh (Maricopa people). The Maricopa people are a Yuman tribe that found refuge on O’otham lands in the early 1800s after being displaced by other Yuman tribes who lived along the lower Colorado River. The Pee Posh agreed to contribute and fight alongside O’otham in exchange for a place to resettle. Around 1859, the United States Congress established Gila River as the first reservation in Arizona. The tribe wasn’t federally recognized until 1935. GRIC is also the sister tribe to the Salt-River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, Ak-Chin Indian Community, and the Tohono O’otham Nation (see map below). We share the same culture and traditions including language, but some things are done and spoken differently.

• Arizona, Gila River and Water

Arizona is a unique state not only because of the Grand Canyon, but it is home to twenty-two federally recognized Native American tribes. The federal government and Native American tribes have a very long complicated history but to sum up the relationship, the U.S constitution recognizes tribal nations as “sovereign” governments. This allows tribes to self-govern their own lands and members independent from state and some government control.

In my culture, there is a word we often use called, himthag (way of life or balanced walk in life and it’s pronounced exactly how it’s spelled). Water plays a big role in our himthag and our modern history. Its referenced in some of our legends, creation stories and petroglyphs. Historically, three rivers once flowed through GRIC: the Salt River, the Santa Cruz River and a 65-mile section of the middle Gila River. My ancestors lived along the river and moved with it when it became scarce at times, hence the name “River People”. We use water for ceremonies, to cleanse, to grow food and plants for traditional baskets and other materials. They formed and built the water canals that branch from the Gila River to create water flow through the seven villages. We still use the canals today to distribute water to the community, but most of the water flows underground.

Our lands and water history is complicated but to summarize it in a nutshell, the U.S enacted the Homestead Act in 1862 that made public lands, lands already claimed by Indigenous tribes, to be available to settlers and farmers without payment. This allowed settlers to also divert water sources for irrigation, power production, and domestic use. Because Native Americans weren’t considered citizens back then, we didn’t have input into the law, and we couldn’t rely on the U.S government to protect our rights. The California Gold Rush caused more settlers to cross O’otham territory in Southern Arizona to get to California. Some of those who migrated to California settled in the southwest and took the land for themselves. It resulted in the Gila River being cut off in the late 1800s which caused mass famine and starvation to O’otham between 1880-1920s. Through this injustice, the U.S government stepped in and provided the people with canned and processed foods which changed diets causing new health diseases of obesity and diabetes.

My tribe is resilient as we found ways to cope by finding work off-reservation and selling some resources such as cutting down mesquite trees for firewood. It also caused some members to migrate to other portions of the river such as the Salt River valley resulting in sister tribes, but the water didn’t last long and met the same fate as the Gila River.

Water slowly started to come back to the reservation restoring some farming practices and introducing running water in homes. GRIC and the Tohono O’otham Nation started their legal battle for water rights to the Gila and Salt Rivers in 1925. There were a lot of false promises, negotiations, and agreements with our neighbors within the span of over 70 years. If you are interested in reading more, check out this link for a thorough GRIC water history. In 2004, GRIC won their case in court resulting in the Arizona Water Settlement Act of 2004, the largest Indian Water settlement in U.S history so far. The act provides the community a water budget of 653,500 acre-feet of water annually. The water comes from the Central Arizona Project (Colorado River water), the Gila River, the Salt River, and groundwater.

The settlement not only brought water, but it provided money to rebuild a better water distribution system to cover the entire reservation and pay for the delivery of water from the Central Arizona Project. Today, our agriculture heritage has been restored, running water is available for domestic use and houses were upgraded to the homes we see today. We are a thriving community with close ties to the land.

• Traditional homes of O’otham were called “Ki” or “olas ki” and were made from branches of arrow weed, cattail, sometimes mud, wheat straw or corn stalks. This picture is from the 1930’s.

• Mud houses were the O’otham’s version of a modern home before transitioning to houses we have today. Fun fact: In grade school, I lived in a mud house until 2004 when it was renovated – no mud.

Life in the Desert

• Maricopa Village is where you can find the only portion of the Gila River that flows. This is where the Gila River meets the Salt River.

• The desert and the Sacaton mountains

Arizona gets about 299 days of sun per year. Arizona’s climate also varies in different parts of the state from arid to semi-arid. Where I am in the Sonoran Desert, it is mostly hot and dry. Depending on where one is at in Arizona, temperatures range from 69° F/43°C to 118° F/47° C. During the months of May – September especially during the monsoon season is when southern Arizona feels the most heat ranging from 90° F - 120°F. Even at night, there isn’t nighttime relief because temperatures remain in the 100° until late August where it drops to cooler temperatures. We also get the most heat warnings during the summer. In Northern Arizona, temperatures are cooler ranging from 19° F to 88° F. The state has been in a twenty-six-year long drought, but we did see a good amount of rain this year. Most of the rain falls during the monsoon season which is between the months of July – September and receives about three – eight inches of rain per year. Areas like the White Mountains in east central Arizona receive about 40 inches of rain.

Most homes today have an air conditioning unit to keep Arizona residents cool in the desert. If one wants to escape the heat, there are lakes, waterfalls and creeks to visit like the Colorado River that is Lake Havasu and Havasupai Falls for those who like to hike. Before air conditioning was introduced to my people, we relied on the shade from the mesquite or cottonwood trees or sat under a va:tho (a shade structure made of tree poles and arrow weed plant placed on the top – open on all sides) to keep cool. I don’t know too much about a ki or an olas ki but I do remember hearing that they stayed cool inside them through the wind that came through the cracks of the branches. Those who lived in mud houses relied on open windows and wetting the floor to cool the inside of the home. Some used swamp evaporative coolers to provide extra cooling inside. I also learned from a World War II veteran, that the O’otham had ways of avoiding dehydration like putting small rocks in their mouth to keep it wet until they can get to safe drinking water and spit it out.

• Farming land with wild horses looking for water and food. Horses have been displaced because of the expansion of cities and new roadways. They are protected in my community, but they can be a nuisance.

Energy and Food Sources

Arizona’s main sources of energy come from natural gas, crude oil, nuclear, and coal. Arizona is also home to the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station which is the largest nuclear power plant in the U.S. It generates more than 32 million megawatt-hours of electricity a year and provides energy to about 4 million people in four states.

Gila River owns its own electric company called Gila River Indian Community Authority Utility (GRICUA). Its main source of energy comes from natural gas with 12% of it coming from hydropower (Hoover Dam). A small portion of less than -5% comes from solar power which powers some streetlights, parking shades and some lights at schools, and public buildings in the community.

GRIC is known for its farming practices as we grew varieties of beans, squash, wheat, and other crops. We still farm today but not how we used to. The Gila River Farms grows many crops from alfalfa, citrus, cotton, wheat, and olives but most of the crops are exported and sold to local, national, and global markets. The farms only provide citrus to community members. Most members shop at local grocery stores or visit farmers markets to purchase fruits and vegetables. Some members garden in their backyards or rely on local farmers who grow and sell crops of hu:n (squash) and different varieties of bav (tepary beans). The tepary bean is one of four ancient crops in our homelands. It is drought tolerant, and it is used in many of our traditional dishes.

Other members who stick close to traditional practices still forage. The Sonoran Desert has tons of edible food and medicines that we still use today and have been beneficial during the pandemic when store shelves were empty. We forage from different varieties of mesquite trees: velvet and honey mesquite, the palo verde tree, kuavol (or wolfberry), hashan biathag (saguaro fruit), and cholla buds to name a few. In my culture, our calendar year doesn’t begin in January. It begins in June during the Summer solstice and our months are named after the budding of plants and trees.

Sustainability and Food Waste in My Household

• Mesquite pods foraged from a velvet and honey mesquite trees

• Foraged saguaro fruit from a saguaro cactus

Learning about sustainability and my O’otham Himthag, encouraged me to start incorporating some of those practices into my everyday life. I learned how to forage with my cousin Alyssa who runs her own traditional food business called Alyssa’s Kosin on the reservation (rez). We go on foraging adventures during budding seasons especially during mesquite season where we pick the pods and use them to make our own syrup and sometimes flour for muffins or cookies. All leftover scraps can be composted or fed to insects or other wildlife. Depending on where the trees are located, it doesn’t take many sources of energy to walk and pick from the trees all around the rez. If one must travel to forage, they would be burning less than a quarter tank of gasoline to get to the areas where mesquite trees are abundant.

• Alyssa and I foraged velvet mesquite this past summer and made mesquite syrup for our families.

Our everyday human activities such as driving, gardening, and using electricity all emit greenhouse gases whether that is directly or indirectly. When it comes to food waste, the food that we don’t eat is thrown into the landfill where it sits, rots, and emits methane (CH4) which is a greenhouse gas powerful than carbon dioxide (Co2) at trapping heat in the atmosphere. Methane accounts for about 16% of global emissions while 84% of it comes from CO2, nitrous oxide (N20), and Fluorinated gases (F-gases).

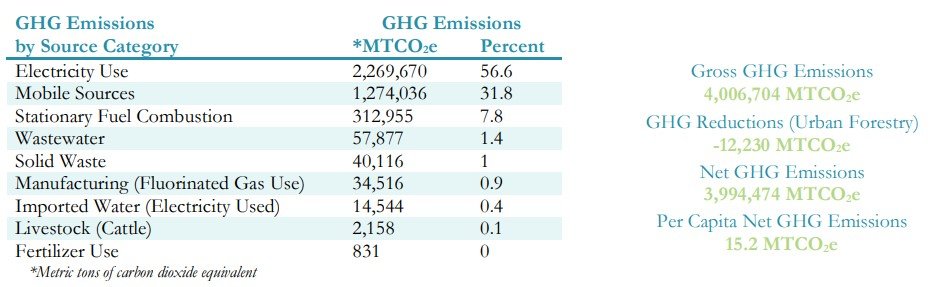

In the United States, methane accounted for 10.1 percent of overall U.S greenhouse gas emissions with 89.9 percent from carbon dioxide and other gasses in 2019. 17.4% of methane came from landfills which is the third-largest source of methane after natural gas systems and cattle livestock populations. In narrowing those numbers down to where I live on the border of the rez and the city Chandler, 519 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCO2e) of greenhouse gases were generated from landfills. There wasn’t much data on residential waste or data from GRIC, but methane generated by solid waste in Chandler is 40,116 MTCO2e.

• Chandler, AZ greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions Inventory for 2018. Source

According to the U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA), food waste accounts for 30-40 percent of the US food supply. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) estimates 63.1 million tons of food waste was generated from commercial, institutional, and residential in 2018.

A solution to reducing the greenhouse gases in my area especially methane from food waste ending up in landfills is composting. Food scraps, napkins, yard waste, and other organic matter can be broken down and turned into nutrient-rich soil that can be used for plants and growing our own food. Composting reduces the need for chemical fertilizers, remediates contaminated soils, and is cost saving to name a few. According to the US EPA, 2.6 million tons of food (41 percent of wasted food) was composted in 2018. Americans were able to recover almost 25 million tons of food through composting which is about 0.42 pounds per person per day for composting.

In my home, I have four family members with the addition of two more who visit every other day for dinner. So, there is a good amount of waste generated in my household from food, plastic, and landfill waste.

• Indoor bins: The brown 13-gallon trash bin in my kitchen holds an average of 10-14 pounds of waste. The red recycling box holds about 13-15 gallons of recyclable material. The box was going to be recycled years ago but it ended up being our long-term recycle bin. Reduce, reuse, and recycle.

• Outdoor bins: The blue recycle bin holds 96 gallons of recyclable material. The green garbage bin holds 90 gallons of landfill waste and has a weight limit of 175 pounds.

We recycle in my home but when it comes to food waste, it’s still a work in progress. Food in my culture brings people together. In my family, we love to cook together and at times valuable food scraps go into the trash bin. Composting is nothing new to me and my family. The only thing that makes it different is the method. I grew up learning from my grandma to only compost vegetable and fruit scraps and shredded newspaper or cardboard, but she didn’t throw it in a pile or bucket. She threw it under a tree or mixed it with the soil where her plants were and watered it. With four curious dogs, I know that I can’t use this method around my home. Due to the pandemic and being quarantined last year, it allowed me free time to create space in my backyard to start a compost pile to make soil for later use. I began with a four-walled gate around my compost pile, but it only lasted two months because the smell attracted my dogs, and they kept digging around it. I continued to give it another try and put chicken wire fencing around the gate pinning it all to the floor with sod staples, but they still found their way in along with other critters. So, I purchased a compost tumbler for $60 to help keep the dogs out. It holds up to 40 pounds of organic matter. So far, it has been able to keep my dogs away.

• Kitchen compost container

•-

It took a while for my family members to participate and take their scraps to the composting pile outside. To make things easier, we designated an empty coffee can as our indoor compost container and later upgraded it to a bigger container to hold more scraps once everyone got into the habit of using it and dumping it into the tumbler outside. After a lot of trial, error, and research, it took about two and a half to three months for our food scraps and yard trimmings to turn into soil.

I don’t know too much about how my ancestors dealt with food waste but from what I know they didn’t waste anything. O’otham were generous and they shared gardens and food with everyone. They saved seeds and threw scraps back into the garden to treat the soil. When they foraged, they never picked more than what they needed. They always picked from the branches and never collected from the ground because the fallen stuff belonged to insects, birds, and other critters. Some animals and wildlife are significant in our himthag and leaving food for them so they can eat was also practiced.

When I began composting, the soil was my main goal than reducing pollution. In our compost bin, we throw in vegetable and fruit scraps sometimes bread, napkins, coffee grounds, tea bags without the staple, cardboard scraps, and yard trimmings. We don’t throw meat, chicken, dairy, or other foods into the bin. From observing the weight of my composting container each day for a week, my family averages about one and a half to two pounds of food waste per day.

To calculate how much food waste, I am diverting from the landfill, I divided the weight of my compost by the weight of all waste in my 13-gallon trash bin to see how much pollution I am saving when I compost.

2 pounds of compost / 15 pounds of all waste in the kitchen bin = 0.13 * 100 = 13.3% of food waste diverted from the landfill each day.

With the addition of worms to my compost, I hope to produce more compost in less time and use it for the raised garden bed I’m building.

Stay tuned.

Sources:

Climate - Arizona State Climate Office (asu.edu)

History About (gilariver.org)

Drought - Arizona State Climate Office (asu.edu)

E:\PUBLAW\PUBL451.108 (congress.gov)

Tribal Governance | NCAI

Homestead Act - Definition, Dates & Significance - HISTORY

Pima-Maricopa Irrigation Project (gilariver.com)

Arizona - State Energy Profile Overview - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

Reducing the Impact of Wasted Food by Feeding the Soil and Composting | US EPA

Food Waste FAQs | USDA

GHG_Inventory_Report_Chandler-PDF (maricopa.gov)

Microsoft Word - GHG_Inventory_Report_Draft_v9.docx (maricopa.gov)

Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2019 – Executive Summary (epa.gov)

Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data | US EPA

Photo Source: Google Images, Gila River Indian Community (gricnews.org) and Personal Images